Search -

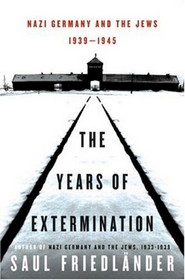

The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945

The Years of Extermination Nazi Germany and the Jews 19391945

Author:

From Publishers Weekly: — In the second volume of his essential history of Nazi Germany and the Jews, one of the great historians of the Holocaust provides a rich, vivid depiction of Jewish life from France to Ukraine, Greece to Norway, in its most tragic period, drawing especially on hundreds of diaries written by Jews during their ordeal, depic... more »

Author:

From Publishers Weekly: — In the second volume of his essential history of Nazi Germany and the Jews, one of the great historians of the Holocaust provides a rich, vivid depiction of Jewish life from France to Ukraine, Greece to Norway, in its most tragic period, drawing especially on hundreds of diaries written by Jews during their ordeal, depic... more »

ISBN-13: 9780060930486

ISBN-10: 0060930489

Publication Date: 4/1/2008

Pages: 896

Rating: 2

ISBN-10: 0060930489

Publication Date: 4/1/2008

Pages: 896

Rating: 2

4.5 stars, based on 2 ratings

Genres: