Helpful Score: 1

I appreciate Jennifer Chiaverini novels because she makes history come alive by weaving facts into fiction with excellent writing. As an elections coordinator, I'm passionate about citizens exercising their right to vote and am interested in the history of voting rights and the voting process.

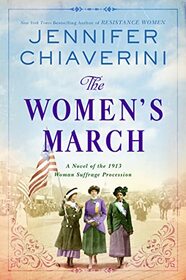

This novel shares the story of three important women in US suffrage history, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Maud Malone, and Alice Paul, and their role in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession that was held in Washington DC one day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Each woman had a unique role in the US women's suffrage movement, and it was fascinating to learn their life stories and their incredible dedication to this important cause that impacts the lives of countless women in the past, today, and in the future. This book was highly readable and completely engrossing.

Every American woman should read this novel to appreciate the history that led to the right to vote for us. Thank you to William Morrow for the review copy; all thoughts are my own.

This novel shares the story of three important women in US suffrage history, Ida B. Wells-Barnett, Maud Malone, and Alice Paul, and their role in the 1913 Woman Suffrage Procession that was held in Washington DC one day before President Woodrow Wilson's inauguration. Each woman had a unique role in the US women's suffrage movement, and it was fascinating to learn their life stories and their incredible dedication to this important cause that impacts the lives of countless women in the past, today, and in the future. This book was highly readable and completely engrossing.

Every American woman should read this novel to appreciate the history that led to the right to vote for us. Thank you to William Morrow for the review copy; all thoughts are my own.

Helpful Score: 1

Jennifer Chiaverini's The Women's March is a fact-based novel centering around the drive to plan and complete a massive march in support of women's suffrage on the day before Woodrow Wilson's 1913 presidential inauguration.

It suffers from being simultaneously too broad and too narrow in viewpoint. The drive for women's suffrage in the U.S. extended from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920 (and in some senses it continues today as the struggle for a definitive Equal Rights Amendment continues to wax and wane). A single work could hardly be expected to hit even the high points of such a long and complex issue, so Chiaverini has concentrated on the period surrounding the 1912 presidential campaign and the early days of the Wilson presidency. In order for the story to make sense, however, she has had to backfill 64 years of the struggle, and to provide an overview of the movement as it existed during the period on which she is concentrating. This introduces a huge and complex cast of characters, organizations, and social issues.

Meantime, she is also narrowing in on three major historical characters â suffrage amendment supporter Dr. Alice Paul, of New Jersey, workers' rights advocate Maud Malone of New York, and pioneering Black journalist and community organizer Ida B. Wells-Barnett of Chicago. Of these three women, Wells-Barnett is easily the most compelling, yet her story is more parallel to that of the other two characters in its narrow focus on the women's march of 1913.

There's a lot of Sturm und Drang here regarding internecine strife among the various factions of the suffrage movement, and entirely too much ink devoted to who wore what at which event. More serious, more compelling, and ultimately much more disturbing, is the bone-deep racism and classism of much of the movement, reaching all the way back to the Seneca Falls meeting and its refusal to invite Sojourner Truth even as it courted and featured Frederick Douglass. Most of us would like our heroes to be ⦠well, heroic ⦠and it's beyond disturbing to see the leaders of the various factions squabbling over who got to be center stage while at the same time continuing to deny full participation by women of color in order to appease racist elements from the Jim Crow south. Their excuse â ranging all the way back to Susan B. Anthony â was that it would be inappropriate to endanger political and social acceptance of votes for women if the issue were â you should excuse the expression â muddied by an insistence on including women of color within that group. This is largely what makes Wells-Barnett's part of the story so compelling. One could wish that the focus had been on this stubborn, brilliant, heroic woman.

Chiaverini, however, has chosen a wider canvas, and her title â The Women's March â works on several layers, as it describes the whole of the movement, the pre-inaugural parade, and a lesser-known but equally ambitious 250-mile foot march from New York to Washington D.C. undertaken as a half-publicity stunt, half-public declaration of intent by a group of women known as âThe Army of the Hudsonâ. Together, the New Yorkers and the women from across the nation who determined to force Wilson into a public declaration of his stance on the issue, formed what Chiaverini calls âthe greatest peacetime demonstration ever witnessed in the United Statesâ. Press reports from the event estimate that 5,000 marchers participated in the procession up Pennsylvania Avenue, drawing crowds of up to 250,000. Along the way, they battled inadequate crowd control, physical assault from anti-suffrage supporters, and a determined silence from Wilson, whose racist and sexist attitudes would ultimately permeate his administration. Over a hundred of the marchers were hospitalized with injuries, many of them sustained while members of the D.C. police force stood by and refused to intervene. And in an unintended but eerie mirroring of events that would occur 109 years later within a stone's throw of the marchers' route, some of the most violent attackers âwrote to brag that they had joined in the mayhem and had no regretsâ.

The more things change, the more it seems they stay the same.

Overall, The Women's March is a valiant attempt, but it remains a heavy lift for any reader. Only those who are intensely interested in this microcosm of the long struggle for equal voting rights will get much more out of it than some inspiration for further reading.

It suffers from being simultaneously too broad and too narrow in viewpoint. The drive for women's suffrage in the U.S. extended from the Seneca Falls Convention in 1848 to the adoption of the 19th Amendment in 1920 (and in some senses it continues today as the struggle for a definitive Equal Rights Amendment continues to wax and wane). A single work could hardly be expected to hit even the high points of such a long and complex issue, so Chiaverini has concentrated on the period surrounding the 1912 presidential campaign and the early days of the Wilson presidency. In order for the story to make sense, however, she has had to backfill 64 years of the struggle, and to provide an overview of the movement as it existed during the period on which she is concentrating. This introduces a huge and complex cast of characters, organizations, and social issues.

Meantime, she is also narrowing in on three major historical characters â suffrage amendment supporter Dr. Alice Paul, of New Jersey, workers' rights advocate Maud Malone of New York, and pioneering Black journalist and community organizer Ida B. Wells-Barnett of Chicago. Of these three women, Wells-Barnett is easily the most compelling, yet her story is more parallel to that of the other two characters in its narrow focus on the women's march of 1913.

There's a lot of Sturm und Drang here regarding internecine strife among the various factions of the suffrage movement, and entirely too much ink devoted to who wore what at which event. More serious, more compelling, and ultimately much more disturbing, is the bone-deep racism and classism of much of the movement, reaching all the way back to the Seneca Falls meeting and its refusal to invite Sojourner Truth even as it courted and featured Frederick Douglass. Most of us would like our heroes to be ⦠well, heroic ⦠and it's beyond disturbing to see the leaders of the various factions squabbling over who got to be center stage while at the same time continuing to deny full participation by women of color in order to appease racist elements from the Jim Crow south. Their excuse â ranging all the way back to Susan B. Anthony â was that it would be inappropriate to endanger political and social acceptance of votes for women if the issue were â you should excuse the expression â muddied by an insistence on including women of color within that group. This is largely what makes Wells-Barnett's part of the story so compelling. One could wish that the focus had been on this stubborn, brilliant, heroic woman.

Chiaverini, however, has chosen a wider canvas, and her title â The Women's March â works on several layers, as it describes the whole of the movement, the pre-inaugural parade, and a lesser-known but equally ambitious 250-mile foot march from New York to Washington D.C. undertaken as a half-publicity stunt, half-public declaration of intent by a group of women known as âThe Army of the Hudsonâ. Together, the New Yorkers and the women from across the nation who determined to force Wilson into a public declaration of his stance on the issue, formed what Chiaverini calls âthe greatest peacetime demonstration ever witnessed in the United Statesâ. Press reports from the event estimate that 5,000 marchers participated in the procession up Pennsylvania Avenue, drawing crowds of up to 250,000. Along the way, they battled inadequate crowd control, physical assault from anti-suffrage supporters, and a determined silence from Wilson, whose racist and sexist attitudes would ultimately permeate his administration. Over a hundred of the marchers were hospitalized with injuries, many of them sustained while members of the D.C. police force stood by and refused to intervene. And in an unintended but eerie mirroring of events that would occur 109 years later within a stone's throw of the marchers' route, some of the most violent attackers âwrote to brag that they had joined in the mayhem and had no regretsâ.

The more things change, the more it seems they stay the same.

Overall, The Women's March is a valiant attempt, but it remains a heavy lift for any reader. Only those who are intensely interested in this microcosm of the long struggle for equal voting rights will get much more out of it than some inspiration for further reading.