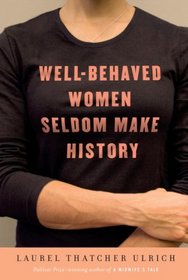

Ulrich, who coined the title phrase in a 1976 scholarly article, spends a fair amount of time here discussing how it took on a life of its own, before settling down to explain what she meant.

The problem, she says, is not that well-behaved women *don't* make history, but that historians haven't done a very good job of reporting on their achievements. Late 20th-century feminists have pretty well created women's history as a legitimate field of study, less through excavation of potshards than through the patient tracking down of those faint records left in letters, journals, and oral history which show ordinary women doing what needed to be done, and building much of the world we recognize today.

She also takes a look at some less-well-behaved women -- Christine de Pizan, who wrote 'The Book of the City of Ladies' at a time when most women not only did not write -- they did not read; abolitionist and women's suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and protofeminist writer Virginia Woolf.

There are passing mentions of many notable points and individuals in the first feminist movement of the mid-19th century, and the "second wave" that came along 100 years later, but few are handled in great detail. The book does, however, provide an excellent jumping-off point for further reading with extensive source notes.

The problem, she says, is not that well-behaved women *don't* make history, but that historians haven't done a very good job of reporting on their achievements. Late 20th-century feminists have pretty well created women's history as a legitimate field of study, less through excavation of potshards than through the patient tracking down of those faint records left in letters, journals, and oral history which show ordinary women doing what needed to be done, and building much of the world we recognize today.

She also takes a look at some less-well-behaved women -- Christine de Pizan, who wrote 'The Book of the City of Ladies' at a time when most women not only did not write -- they did not read; abolitionist and women's suffrage leader Elizabeth Cady Stanton; and protofeminist writer Virginia Woolf.

There are passing mentions of many notable points and individuals in the first feminist movement of the mid-19th century, and the "second wave" that came along 100 years later, but few are handled in great detail. The book does, however, provide an excellent jumping-off point for further reading with extensive source notes.