Search -

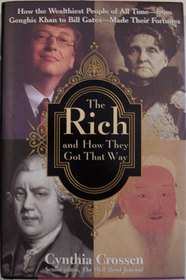

The Rich and How They Got That Way: How the Wealthiest People of All Time--from Genghis Khan to Bill Gates--Made Their Fortunes

The Rich and How They Got That Way How the Wealthiest People of All Timefrom Genghis Khan to Bill GatesMade Their Fortunes

Author:

What does Bill Gates have in common with Genghis Khan, the thirteenth-century conqueror who wanted to own the world but settled for just five million square miles? — Or, for that matter, what does Gates have to do with Pope Alexander IV, whom historians describe as a scoundrel, saint, charlatan, and samaritan? Or Richard Arkwright, the eighteenth... more »

Author:

What does Bill Gates have in common with Genghis Khan, the thirteenth-century conqueror who wanted to own the world but settled for just five million square miles? — Or, for that matter, what does Gates have to do with Pope Alexander IV, whom historians describe as a scoundrel, saint, charlatan, and samaritan? Or Richard Arkwright, the eighteenth... more »

ISBN-13: 9780812932676

ISBN-10: 0812932676

Publication Date: 7/18/2000

Pages: 320

Rating: ?

ISBN-10: 0812932676

Publication Date: 7/18/2000

Pages: 320

Rating: ?

0 stars, based on 0 rating

Genres:

- Biographies & Memoirs >> General

- Biographies & Memoirs >> People, A-Z >> ( G ) >> Gates, Bill

- Business & Money >> General

- Business & Money >> Personal Finance >> General

- Business & Money >> Business Development & Entrepreneurship >> Entrepreneurship