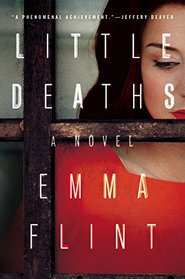

First I'll say this--I did not know it was based on a true story

I think this is a well written story and it captured my attention from the beginning, I'm glad I didn't know it was based on a true story as it just makes for a good story, now the other reviewer I understand where she is coming from and maybe this book doesn't get the 'true' facts right but then maybe she didn't mean to and instead tried to make it another interesting story for readers like me

I'm giving it all 5* as I thought it was well written

I think this is a well written story and it captured my attention from the beginning, I'm glad I didn't know it was based on a true story as it just makes for a good story, now the other reviewer I understand where she is coming from and maybe this book doesn't get the 'true' facts right but then maybe she didn't mean to and instead tried to make it another interesting story for readers like me

I'm giving it all 5* as I thought it was well written

I remember the Alice Crimmins case. Although I was only 12 years old at the time, the horror of it obsessed anyone who could pick up a newspaper in Queens, NY-- two small children dead, their "no better than she should be" mother tried and found guilty in the court of public opinion, the press and police force relying more on their "gut instincts" and prejudices than on real evidence.

So I was very curious to read this fictionalized account of the events of July, 1965, especially after reading reviews that describe it as profound and insightful. But I feel that this is another example of a novelist who has taken on a real-life story and failed to get the balance between the facts and the fiction right.

Up until about mid-way through the novel, Flint only very lightly fictionalizes the characters and events of July 1965. Names are changed, but the setting, the circumstances, the inexorable wheels of injustice and assumption that ground Alice Crimmins down are (to the best of my knowledge) exactly as it happened. Flint does a very good job of capturing those circumstances: the hot, breathless summer; the working class neighborhood, only yards from the boundary fences of the 1965 World's Fair; the nosy neighbors, and the soul-crushing expectations of respectability, beauty and yearning for a better life.

Where it all starts to go wrong is when Flint starts inventing wholesale: a young would-be journalist falls in love with Alice, and is determined to save her. The mystery, "whodunit," is solved thanks to the young journalist's sleuthing, as if this an Agatha Christie novel, or a "very special episode" of "Midsomer Murders." In my opinion, there is a "so what" quality to both the romance and the solution. It feels like Flint is asking the wrong questions.

The question I always ask myself, as I'm reading a fictionalized version of real-life events, is why? Why am I reading this, and what am I getting from the fiction that I couldn't get from a well-written and researched history or biography? This is a crime that has been investigated over and over again, in reality and in fiction. Found guilty three times by a jury of her peers, Crimmins served over two years in prison before, three times, her convictions were quashed due to profound legal faults. There have been true crime books, documentaries, and movie of the week dramatizations, good bad and indifferent. And fifty years later, the questions remain: did Alice Crimmins kill her children? And if not, who did? And what do her prosecutions say about our attitudes to women who are deemed guilty of being ânot good enoughâ mothers?

So I was very curious to read this fictionalized account of the events of July, 1965, especially after reading reviews that describe it as profound and insightful. But I feel that this is another example of a novelist who has taken on a real-life story and failed to get the balance between the facts and the fiction right.

Up until about mid-way through the novel, Flint only very lightly fictionalizes the characters and events of July 1965. Names are changed, but the setting, the circumstances, the inexorable wheels of injustice and assumption that ground Alice Crimmins down are (to the best of my knowledge) exactly as it happened. Flint does a very good job of capturing those circumstances: the hot, breathless summer; the working class neighborhood, only yards from the boundary fences of the 1965 World's Fair; the nosy neighbors, and the soul-crushing expectations of respectability, beauty and yearning for a better life.

Where it all starts to go wrong is when Flint starts inventing wholesale: a young would-be journalist falls in love with Alice, and is determined to save her. The mystery, "whodunit," is solved thanks to the young journalist's sleuthing, as if this an Agatha Christie novel, or a "very special episode" of "Midsomer Murders." In my opinion, there is a "so what" quality to both the romance and the solution. It feels like Flint is asking the wrong questions.

The question I always ask myself, as I'm reading a fictionalized version of real-life events, is why? Why am I reading this, and what am I getting from the fiction that I couldn't get from a well-written and researched history or biography? This is a crime that has been investigated over and over again, in reality and in fiction. Found guilty three times by a jury of her peers, Crimmins served over two years in prison before, three times, her convictions were quashed due to profound legal faults. There have been true crime books, documentaries, and movie of the week dramatizations, good bad and indifferent. And fifty years later, the questions remain: did Alice Crimmins kill her children? And if not, who did? And what do her prosecutions say about our attitudes to women who are deemed guilty of being ânot good enoughâ mothers?