For most of my life I have been into recycling, reusing and composting. In some ways I do this with an almost religious fervor. I also try to avoid obtaining items which generate unnecessary waste. Fortunately, the government of Alachua County, Florida, where I live, has pretty much the same attitude. In fact, the county has received national awards for its recycling. Unfortunately, that doesn't mean that all county residents support the county's efforts. And this book often points out why that is so.

As a result, I found this book a fascinating, but also distressing, read. As the author points out, just because there is a recycling number on plastic, glass and metal containers doesn't mean that container was made from recycled materials or will be recycled itself. The container industry supports the concept of marking things as recyclables because it makes the consumer feel good, and not understand that the container industry needs to keep making disposable containers to make a profit.

Did you know the major trash collection corporations make more profit from selling landfill space than by collecting trash? This means that recycling materials instead of burying them in a landfill reduces their profit. But they don't want you to know that.

The author covers the growth of the three or four major corporations which control trash collection in the U.S. These corporations can almost dictate the costs of such collection to every local government entity. I found it interesting how these corporations would undercut local trash firms to take over their city contracts, then raise their prices when those firm are driven out of business. Yet it was the small, local firms which excelled in the recycling process.

I found it interesting how these corporations fought the Mafia, which once controlled trash collection in New York City, while reaping huge profits. The corporations had a fight on their hands which they eventually won, but then tuned around, raised their prices and reaped those same profits.

The author covers the history of trash, and shows how for centuries it made economic sense to reuse that trash. But that all changed with the Industrial Revolution. Corporations make their profit by you buying more stuff to throw away, so you'll buy even more.

Sometimes, when I see the amount of trash people throw away, I wonder if they really love their children and grandchildren. Don't they understand what kind of world they are leaving them? But as the author points out, corporations do a very effective job of making sure consumers don't think about this.

But more states are now enacting deposit laws, which the corporations fight in various ways, including hefty contributions to local and state politicians. In the areas where there are deposits, it has been proven to reduce trash as well as create large numbers of jobs. One argument corporations use is that people will just go to other states to buy items so as to avoid the deposit fees. They even resort to having their own employees pretend to be local citizens. My own state does not have deposit fees, probably due to industry influence. But I wonder how many people in Miami, Tampa, Orlando, Daytona and so many other places in Florida are going to drive to Georgia to buy their soda and beer. Makes you wonder who our local politicians are working for.

As a result, I found this book a fascinating, but also distressing, read. As the author points out, just because there is a recycling number on plastic, glass and metal containers doesn't mean that container was made from recycled materials or will be recycled itself. The container industry supports the concept of marking things as recyclables because it makes the consumer feel good, and not understand that the container industry needs to keep making disposable containers to make a profit.

Did you know the major trash collection corporations make more profit from selling landfill space than by collecting trash? This means that recycling materials instead of burying them in a landfill reduces their profit. But they don't want you to know that.

The author covers the growth of the three or four major corporations which control trash collection in the U.S. These corporations can almost dictate the costs of such collection to every local government entity. I found it interesting how these corporations would undercut local trash firms to take over their city contracts, then raise their prices when those firm are driven out of business. Yet it was the small, local firms which excelled in the recycling process.

I found it interesting how these corporations fought the Mafia, which once controlled trash collection in New York City, while reaping huge profits. The corporations had a fight on their hands which they eventually won, but then tuned around, raised their prices and reaped those same profits.

The author covers the history of trash, and shows how for centuries it made economic sense to reuse that trash. But that all changed with the Industrial Revolution. Corporations make their profit by you buying more stuff to throw away, so you'll buy even more.

Sometimes, when I see the amount of trash people throw away, I wonder if they really love their children and grandchildren. Don't they understand what kind of world they are leaving them? But as the author points out, corporations do a very effective job of making sure consumers don't think about this.

But more states are now enacting deposit laws, which the corporations fight in various ways, including hefty contributions to local and state politicians. In the areas where there are deposits, it has been proven to reduce trash as well as create large numbers of jobs. One argument corporations use is that people will just go to other states to buy items so as to avoid the deposit fees. They even resort to having their own employees pretend to be local citizens. My own state does not have deposit fees, probably due to industry influence. But I wonder how many people in Miami, Tampa, Orlando, Daytona and so many other places in Florida are going to drive to Georgia to buy their soda and beer. Makes you wonder who our local politicians are working for.

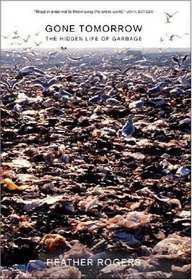

Answers the question of where does it all go? The complex story of trash, because it does not disappear...

An excellent overview of where garbage has been and where garbage is going.