Search -

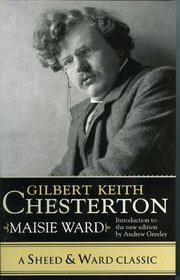

Gilbert Keith Chesterton (Sheed & Ward Classic)

Gilbert Keith Chesterton - Sheed & Ward Classic

Author:

a selection from Chapter 10 - Who is G.K.C.? THE BOER WAR--and the whole country enthusiastically behind it. The Liberal Party as a whole went with the Conservatives. The leading Fabians--Bernard Shaw, Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Webb, Hubert Bland, Cecil Chesterton and the "semi-detached Fabian" H. G. Wells--were likewise for ... more »

Author:

a selection from Chapter 10 - Who is G.K.C.? THE BOER WAR--and the whole country enthusiastically behind it. The Liberal Party as a whole went with the Conservatives. The leading Fabians--Bernard Shaw, Mr. and Mrs. Sidney Webb, Hubert Bland, Cecil Chesterton and the "semi-detached Fabian" H. G. Wells--were likewise for ... more »

ISBN-13: 9780742550445

ISBN-10: 0742550443

Publication Date: 10/28/2005

Pages: 600

Rating: ?

ISBN-10: 0742550443

Publication Date: 10/28/2005

Pages: 600

Rating: ?

0 stars, based on 0 rating

Publisher: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Book Type: Paperback

Members Wishing: 2

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Book Type: Paperback

Members Wishing: 2

Reviews: Amazon | Write a Review

Genres:

- Biographies & Memoirs >> General

- Biographies & Memoirs >> Leaders & Notable People >> Religious

- Literature & Fiction >> General

- Religion & Spirituality >> General

- Religion & Spirituality >> Religious Studies >> Church & State

- Christian Books & Bibles >> Catholicism >> General

- Christian Books & Bibles >> Catholicism >> Roman Catholicism