Helpful Score: 5

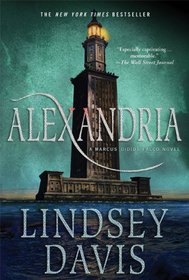

Alexandria is the 19th outing for the intrepid Marcus Didius Falco. Davis writes in the first person and Falco is our amiable and sardonic guide. The wryly witty Falco has grown assured and comfortable with himself over the years. He's married now and the father of 2 girls with a third child on the way. His wife, Helena Justina, is the daughter of a Roman senator and he greatly respects her and her intelligence. Now, as his personal life has become that of a settled man, a father and a husband, the mysteries have also changed. The last few have seen him and his little family traveling outside Rome to places like Delphi in Greece.

As the book opens, Falco, his little family and his restless brother-in-law Aulus are arriving in Alexandria, still the most valued center of learning in the ancient world. They intend to do some sightseeing and try and get Aulus accepted into the Museion. Rumor says Falco is also here on Vespasian's errand, (before anyone goes running to check, the year is 77AD, about 100 years after the death of Julius Caesar) and more than one person is worried by his presence. Falco's very real vacation plans get sidetracked when the Head Librarian of the Great Library, Theon, a dinner guest at his uncle's house the previous night, is found dead at his desk in a locked office.

The Prefect of Egypt asks Falco to investigate, not a request Falco can refuse. Since the Prefect figures he's already on the Emperor's payroll, he doesn't deserve any extra payment, but the wily Falco gets 'expenses'- in advance. By the time Falco gets to the scene of the crime, if a crime it was, the body is gone, the site cleared up and the centurion, Tenax, the man stuck with the initial investigation, is his only 'eye witness' account of the discovery.

Falco's investigation runs smack into the self-important, back-stabbing upper echelon of the Museion. Naturally, like the scholars they are, they start lying immediately, especially Philetus, the Director and technically Theon's boss. Just finding the body sends Falco chasing all over before it was finally admitted there was an illegal necropsy being performed by the head zoo keeper, Philadelphion, and his assistants, Chaereas and Chaeteas. Since it was highly illegal, it was well attended by the students - and Falco and Aulus. (Often at loose ends, Aulus has taken to acting as Falco's assistant, a not very socially acceptable pastime for a senator's son.)

The necropsy shows something that a simple physical examination of the body would not have shown - laurel leaves in Theon's digestive tract. Laurel was woven into the wreaths that his uncle had for his guests the night before, but surely a man as learned as Theon knew not to eat them - unless it was a suicide. Strange time and place for that - and why?

The body count rises and the suspects just keep getting more suspicious. Another chat with the slippery Philetus, Director of the Museion and Theon's nominal boss, yields little, but Falco's parting thoughts are a gem.

"I left thinking how very much I would have liked to see Philetus dead, embalmed and mummified on a dusty shelf. If possible, I would consign him to a rather disreputable temple where they got the rites wrong. He festered. The man was only good for a long eternity of mould and decay."

Falco's sardonic wit cheerfully skewers everyone, even himself. The solution has a twist, which I expected. All in all, it was a very satisfying outing.

You can read a full review here http://toursbooks.wordpress.com/2009/05/29/book-review-alexandria-by-lindsey-davis/

As the book opens, Falco, his little family and his restless brother-in-law Aulus are arriving in Alexandria, still the most valued center of learning in the ancient world. They intend to do some sightseeing and try and get Aulus accepted into the Museion. Rumor says Falco is also here on Vespasian's errand, (before anyone goes running to check, the year is 77AD, about 100 years after the death of Julius Caesar) and more than one person is worried by his presence. Falco's very real vacation plans get sidetracked when the Head Librarian of the Great Library, Theon, a dinner guest at his uncle's house the previous night, is found dead at his desk in a locked office.

The Prefect of Egypt asks Falco to investigate, not a request Falco can refuse. Since the Prefect figures he's already on the Emperor's payroll, he doesn't deserve any extra payment, but the wily Falco gets 'expenses'- in advance. By the time Falco gets to the scene of the crime, if a crime it was, the body is gone, the site cleared up and the centurion, Tenax, the man stuck with the initial investigation, is his only 'eye witness' account of the discovery.

Falco's investigation runs smack into the self-important, back-stabbing upper echelon of the Museion. Naturally, like the scholars they are, they start lying immediately, especially Philetus, the Director and technically Theon's boss. Just finding the body sends Falco chasing all over before it was finally admitted there was an illegal necropsy being performed by the head zoo keeper, Philadelphion, and his assistants, Chaereas and Chaeteas. Since it was highly illegal, it was well attended by the students - and Falco and Aulus. (Often at loose ends, Aulus has taken to acting as Falco's assistant, a not very socially acceptable pastime for a senator's son.)

The necropsy shows something that a simple physical examination of the body would not have shown - laurel leaves in Theon's digestive tract. Laurel was woven into the wreaths that his uncle had for his guests the night before, but surely a man as learned as Theon knew not to eat them - unless it was a suicide. Strange time and place for that - and why?

The body count rises and the suspects just keep getting more suspicious. Another chat with the slippery Philetus, Director of the Museion and Theon's nominal boss, yields little, but Falco's parting thoughts are a gem.

"I left thinking how very much I would have liked to see Philetus dead, embalmed and mummified on a dusty shelf. If possible, I would consign him to a rather disreputable temple where they got the rites wrong. He festered. The man was only good for a long eternity of mould and decay."

Falco's sardonic wit cheerfully skewers everyone, even himself. The solution has a twist, which I expected. All in all, it was a very satisfying outing.

You can read a full review here http://toursbooks.wordpress.com/2009/05/29/book-review-alexandria-by-lindsey-davis/

Helpful Score: 2

For any hardcore Falco fan - like me - this is a must-read ... but maybe not a "keeper". Reading along, I kept being waked up out of that "lost in a book" state with the recurrent thought that "Alexandria" would have benefited by red-penciling by a stern editor. Beyond that, it just wasn't as charming as every other Falco book up to this: more plot-driven than character-driven, with a jarring excess of current British slang. It wasn't even necessary in order to keep up with the life story of Falco et al. A pity, really.

![header=[] body=[Get a free book credit right now by joining the club and listing 5 books you have and are willing to share with other members!] Help icon](/images/question.gif?v=90afaeb39)